|

EAP511S - ENGLISH FOR ACADEMIC PURPOSES DI - 1ST OPP - JUNE 2024 |

|

1 Pages 1-10 |

▲back to top |

|

1.1 Page 1 |

▲back to top |

|

1.2 Page 2 |

▲back to top |

|

1.3 Page 3 |

▲back to top |

|

1.4 Page 4 |

▲back to top |

|

1.5 Page 5 |

▲back to top |

|

1.6 Page 6 |

▲back to top |

|

1.7 Page 7 |

▲back to top |

|

1.8 Page 8 |

▲back to top |

|

1.9 Page 9 |

▲back to top |

|

1.10 Page 10 |

▲back to top |

|

2 Pages 11-20 |

▲back to top |

|

2.1 Page 11 |

▲back to top |

|

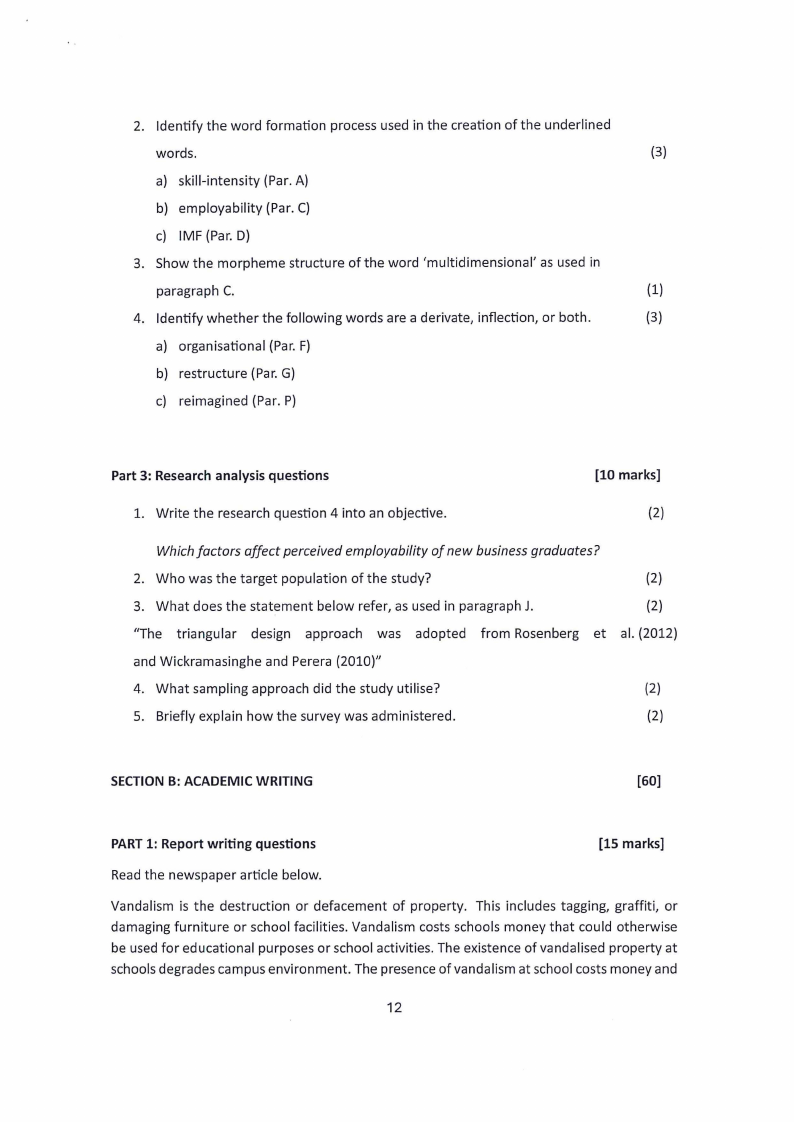

2.2 Page 12 |

▲back to top |

|

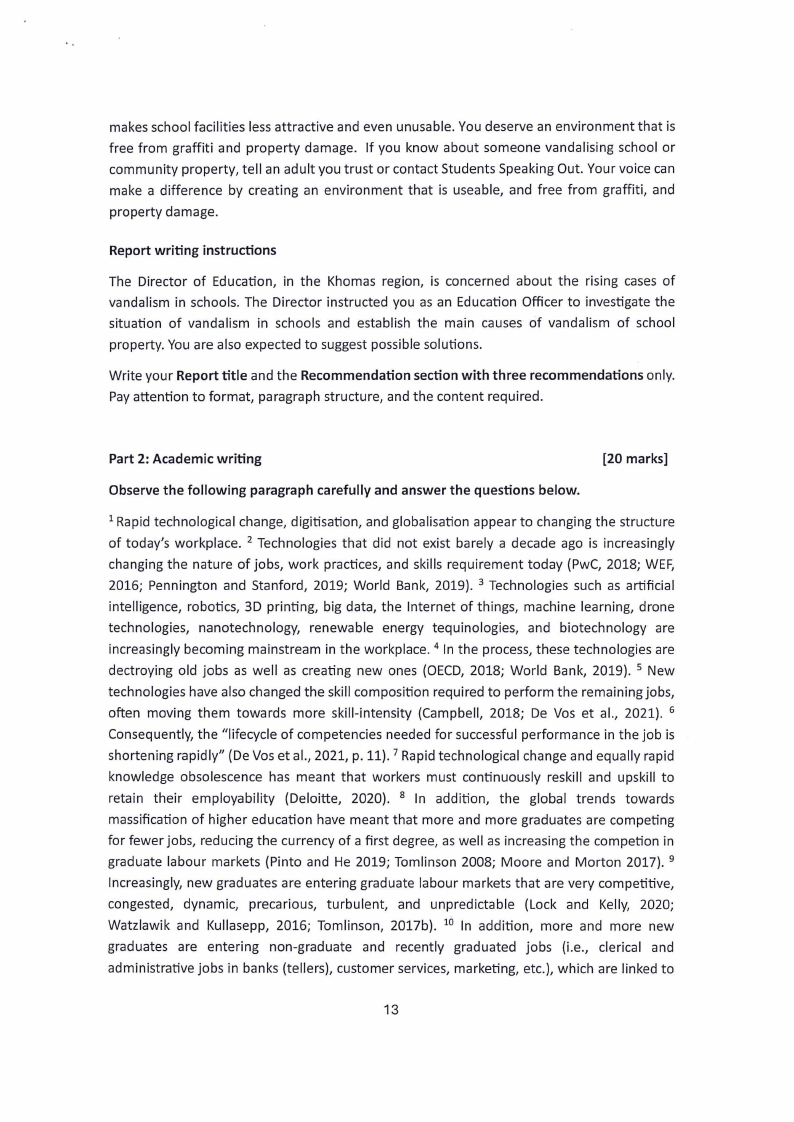

2.3 Page 13 |

▲back to top |

|

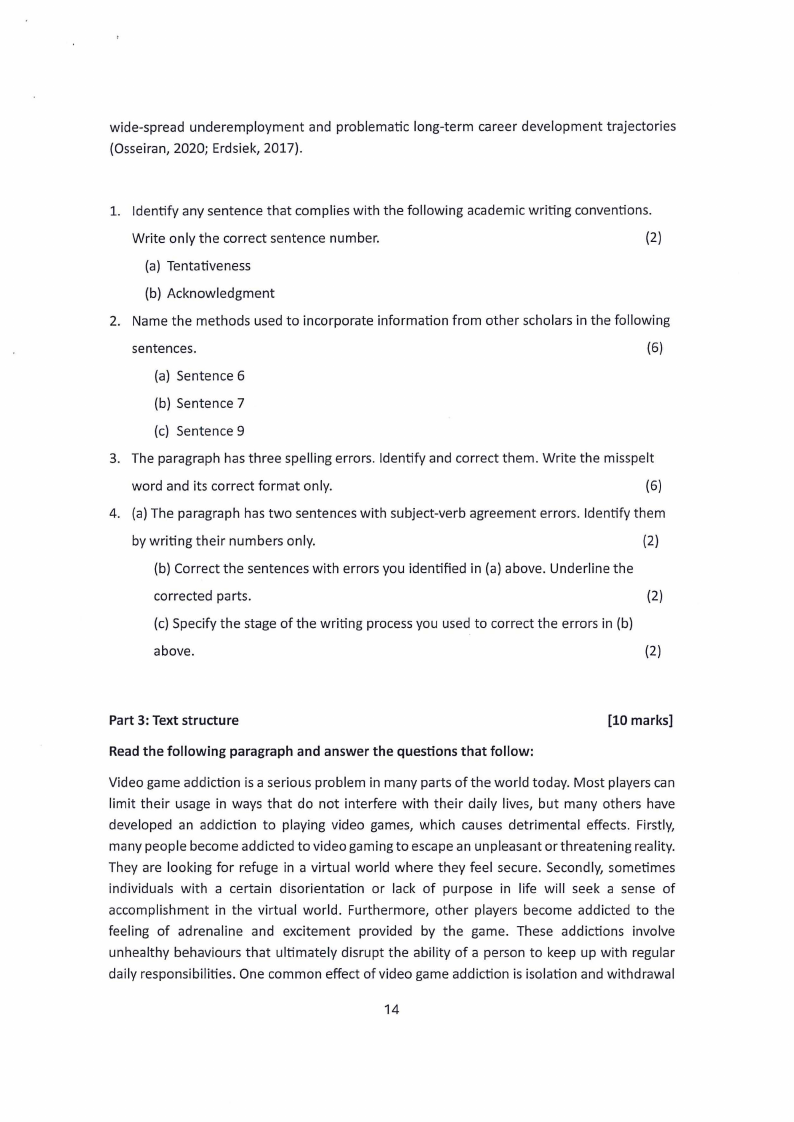

2.4 Page 14 |

▲back to top |

|

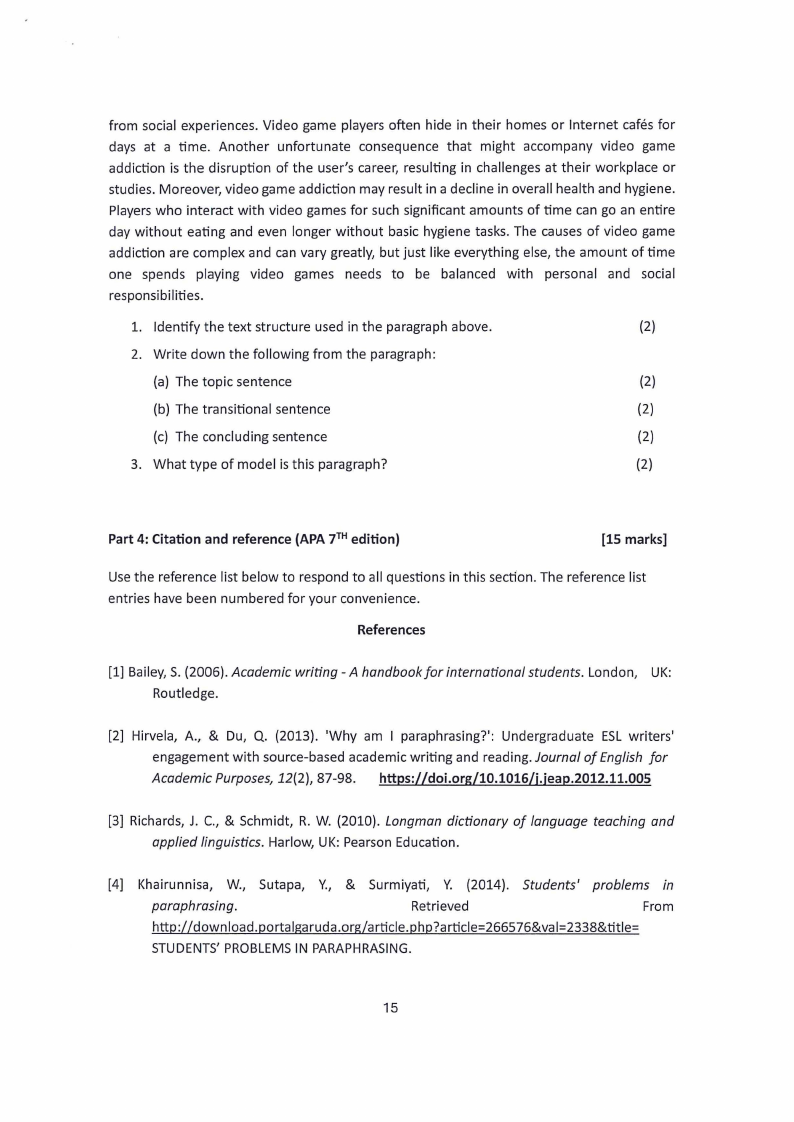

2.5 Page 15 |

▲back to top |

|

2.6 Page 16 |

▲back to top |